His mother has suffered the trauma of two miscarriages, an ectopic pregnancy and 13 failed IVF attempts.

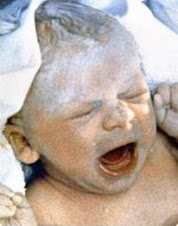

Having been through all that this little baby boy can only be described as her miracle.

The child, identified only as Oliver, has become the first in the world to be born using an IVF technique that is said to more than double the chances of pregnancy.

Oliver, from the south of England, was born in July after doctors devised a way of counting the chromosomes in eggs, allowing them to pick only the best for fertility treatment.

After years of IVF disappointment, his mother, aged 41, had all but given up hope of ever having a baby of her own.

It's hardly surprising that her doctor says the woman and her husband - who have requested privacy - are still in shock at the birth.

Simon Fishel, of the Care group of fertility clinics, said: 'You get to a point where you don't believe it is going to happen to you.

'They are absolutely thrilled, as anybody would be, but believe it is almost more of a miracle in their case because of their history.

'Oliver's birth is an important landmark in shaping our understanding of why many women fail to become pregnant.'

So far, another six or so women have become pregnant thanks to the technique. But in time it could help many more women achieve their dream of motherhood.

Initial studies suggest it can more than double the odds of conception, cutting the cost and heartache of failed IVF attempts.

The technique, known as array comparative genomic hybridisation

Healthy eggs should have 23 chromosomes but many have more or less than this, greatly cutting the chances of pregnancy and raising the risk of miscarriage and of having a child with a condition such as Down's syndrome.

Up to three-quarters of miscarriages are thought to be due to embryos having too many or too chromosomes, with eggs from older women particularly likely to be problematic.

In trials, a more basic form of the technique doubled the pregnancy rate from 25 per cent to 50 per cent.

The latest version, pioneered at Care's Nottingham clinic, removes the potentially risky step of freezing and thawing the eggs or embryos and so could boast even better results.

Dr Fishel said: 'I really don't want to raise hopes unnecessarily but I do believe that because chromosomal abnormalities are so vast in cases of IVF failure that this technique will produce higher live birth rates.

'I am hoping it will double, or even more than double, the chances in most groups of patients.'

Optimising the chances of pregnancy would also allow doctors to reduce the number of eggs they implant in a woman at one time, cutting the odds of risky twin and triplet pregnancies.

The Care team is now trying out the method on embryos, something-that could increase the chances of success even further.

Although the method is mainly being used in women who have repeatedly failed at IVF, younger women could also benefit, as up to half of their eggs have chromosomal problems.

However, the £2,000 price tag, on top of the £3,000 or so for IVF, may put many off.

Experts urged caution about the development.

Tony Rutherford, chairman of the British Fertility Society, said that while the technology offers 'much promise' more research was needed to ascertain its value.

He said: 'The widespread use of this technology should await the outcome of such research to ensure we know which patients might benefit.'

Professor Peter Braude, head of the department of women's health at King's College London, said: 'I am delighted that this patient has achieved her positive outcome after so many years of trying.

'However we need to be cautious as to whether the new technique was responsible.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Monday, September 14, 2009

New IVF test increases pregnancy chances, say researchers

A new technique for screening embryos for genetic defects during IVF more than doubles the chances that the embryo will implant in the mother's womb, according to a pilot study by UK and US researchers.

The method, which has several advantages over an existing screening technique, led to established pregnancies - meaning that foetal heartbeat was detected using ultrasound - in 78% of the 23 women who underwent the treatment. Genetic screening involves testing embryos produced during in-vitro fertilisation for abnormal chromosomes that could prevent the embryos from being carried to term.

Fertility doctors using the current technique take one or two cells at day three of the embryo's development, when it has eight cells. Once healthy embryos have been selected, they are implanted back into the patient's uterus. The technique, fluorescent in situ hybridisation, is controversial, with some studies suggesting that it provides no benefit or is counter-productive. The long-term effects of manipulating the embryo are unknown.

The new technique, called comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH), allows doctors to remove cells from the embryo at a later stage, when it is five days old and has more than 100 cells. Removing cells at this stage should be less damaging, and by analysing five or six cells the clinician can be more confident that the genetic abnormality exists in the whole embryo, and not just a few cells.

The researcher who has developed the new technique is planning to offer it in the UK for about £2,000, on top of the fee for IVF, and around the same as standard screening techniques.

"The pregnancy rates we've got so far are absolutely phenomenal," said Dr Dagan Wells at Oxford University and Reprogenetics UK, who led the study. "We're ready to begin a trial in the UK, and we have a couple of licence applications in to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority to start offering CGH to patients." The HFEA is the UK's regulator of fertility clinics.

Dr Mandy Katz-Jaffe at the Colorado Centre for Reproductive Medicine, near Denver, who is part of the team, said: "The patients who are going through this knew this was their last chance of conceiving without going for donor eggs. They have a poor prognosis, with multiple failed cycles. The effect on those patients who have conceived has been beyond anything I can describe." Wells's team tested the CGH method in 23 women aged 30-42, and transferred 50 embryos. After screening and embryo transfer, 20 of the women became pregnant (foetal heartbeat confirmed by ultrasound).

The method, which has several advantages over an existing screening technique, led to established pregnancies - meaning that foetal heartbeat was detected using ultrasound - in 78% of the 23 women who underwent the treatment. Genetic screening involves testing embryos produced during in-vitro fertilisation for abnormal chromosomes that could prevent the embryos from being carried to term.

Fertility doctors using the current technique take one or two cells at day three of the embryo's development, when it has eight cells. Once healthy embryos have been selected, they are implanted back into the patient's uterus. The technique, fluorescent in situ hybridisation, is controversial, with some studies suggesting that it provides no benefit or is counter-productive. The long-term effects of manipulating the embryo are unknown.

The new technique, called comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH), allows doctors to remove cells from the embryo at a later stage, when it is five days old and has more than 100 cells. Removing cells at this stage should be less damaging, and by analysing five or six cells the clinician can be more confident that the genetic abnormality exists in the whole embryo, and not just a few cells.

The researcher who has developed the new technique is planning to offer it in the UK for about £2,000, on top of the fee for IVF, and around the same as standard screening techniques.

"The pregnancy rates we've got so far are absolutely phenomenal," said Dr Dagan Wells at Oxford University and Reprogenetics UK, who led the study. "We're ready to begin a trial in the UK, and we have a couple of licence applications in to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority to start offering CGH to patients." The HFEA is the UK's regulator of fertility clinics.

Dr Mandy Katz-Jaffe at the Colorado Centre for Reproductive Medicine, near Denver, who is part of the team, said: "The patients who are going through this knew this was their last chance of conceiving without going for donor eggs. They have a poor prognosis, with multiple failed cycles. The effect on those patients who have conceived has been beyond anything I can describe." Wells's team tested the CGH method in 23 women aged 30-42, and transferred 50 embryos. After screening and embryo transfer, 20 of the women became pregnant (foetal heartbeat confirmed by ultrasound).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

| Powered By widgetmate.com | Sponsored By Digital Camera |